Why the plunge was even more severe than the market expected

Original Author: arndxt

Original Translation: SpecialistXBT

In the past few months, my stance has undergone a substantial shift:

From "so bearish that it turns bullish" (an overcrowded pessimism that often sets the stage for a short squeeze), to "bearish and genuinely concerned that the system is entering a more fragile phase."

This was not triggered by a single event, but is based on the following five mutually reinforcing dynamic factors:

1. The risk of policy mistakes is rising. The Federal Reserve is tightening financial conditions due to economic data uncertainty and clear signs of economic slowdown.

2. The AI/mega-cap complex is shifting from cash-rich to leveraged growth. This moves risk from pure equity volatility to more classic credit cycle issues.

3. Private credit and loan valuations are starting to diverge. Beneath the surface, there are early but worrying signs of stress in model-based pricing.

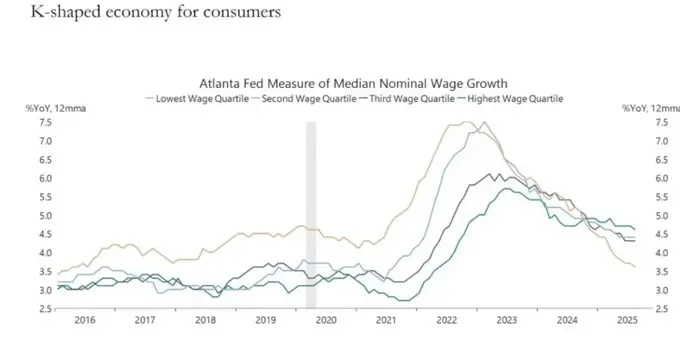

4. The K-shaped economy is solidifying into a political issue. For a growing portion of the population, the social contract is no longer credible; this sentiment will eventually be expressed through policy.

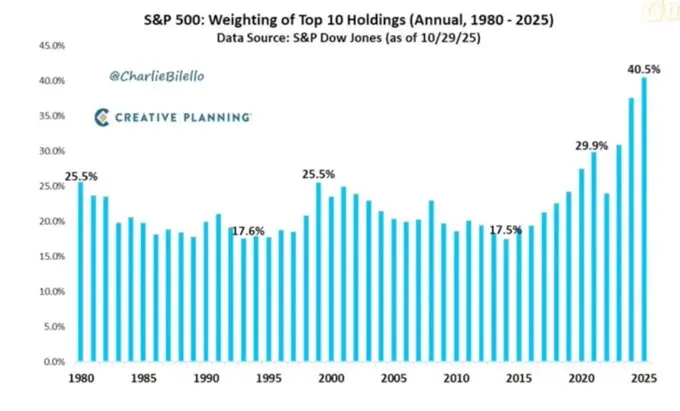

5. Market concentration has become a systemic and political vulnerability. When about 40% of index weight is concentrated in a handful of tech monopolies sensitive to geopolitics and leverage, they are no longer just growth stories, but national security issues and policy targets.

The baseline scenario may still be that policymakers will ultimately "do what they always do": inject liquidity back into the system and support asset prices into the next political cycle.

But the path to this outcome looks bumpier, more credit-driven, and politically less stable than the standard "buy the dip" playbook assumes.

Macro Stance

For most of this cycle, it was rational to hold a "bearish but constructive" stance:

Inflation was high but decelerating.

Policy was broadly still supportive.

Risk asset valuations were high, but pullbacks were usually met with liquidity injections.

Now, several elements have changed:

- Government shutdown: We experienced a prolonged government shutdown, which disrupted the release and quality of key macro data.

- Statistical uncertainty: Senior officials themselves admit the federal statistical system has been damaged, meaning they lack confidence in the statistical series underpinning trillions of dollars in asset allocation.

- Turning hawkish in weakness: Against this backdrop, the Federal Reserve has chosen to turn more hawkish both in rate expectations and balance sheet, tightening financial conditions even as forward-looking indicators deteriorate.

In other words, the system is amplifying uncertainty and stress, rather than escaping it. This is a fundamentally different risk environment.

Policy Tightening in the Fog

The core issue is not just policy tightening, but where and how policy is tightening:

- Data fog: Key data releases (inflation, employment) have been delayed, distorted, or questioned after the shutdown. The Fed's "dashboard" has become unreliable at the most critical moment.

- Rate expectations: Even though forward indicators point to deflation early next year, market-implied odds of near-term rate cuts have been repriced lower as Fed officials make hawkish statements.

Even if policy rates remain unchanged, the balance sheet stance on quantitative tightening and the tendency to push more duration assets into the private sector are essentially hawkish for financial conditions.

Historically, the Fed's mistakes are usually timing errors: tightening too late, easing too late.

We face the risk of repeating this pattern: tightening during slowing growth and data fog, rather than preemptively easing to address these conditions.

AI and Tech Giants Become "Leveraged Growth" Stories

The second structural shift is in the nature of tech giants and leading AI companies:

Over the past decade, the "Mag7" essentially acted like equity bonds: dominant franchises, huge free cash flow, massive buybacks, limited net leverage.

In the past 2-3 years, more and more of this free cash flow has been redirected to AI capital expenditures: data centers, chips, infrastructure.

We are now entering a new phase, where incremental AI capex is increasingly financed by issuing debt, not just internally generated cash.

This means:

Credit spreads and CDS (credit default swaps) are starting to move. As leverage is added to finance AI infrastructure, credit spreads for companies like Oracle are widening.

Equity volatility is no longer the only risk. We now see that sectors once thought "invulnerable" are starting to exhibit classic credit cycle dynamics.

Market structure amplifies this. These names occupy outsized shares of major indices; their shift from "cash cows" to "leveraged growth" changes the risk profile of the entire index.

This does not automatically mean the AI "bubble" will burst. If returns are real and durable, borrowing for capex is rational.

But it does mean the margin for error is smaller, especially in a higher-rate, tighter policy environment.

Signs of Fault Lines in Credit and Private Markets

Beneath the surface of public markets, private credit is showing early signs of stress:

The same loan is being valued very differently by different managers (e.g., one values it at 70 cents, another at about 90 cents).

This divergence is a classic precursor to broader disputes between model-based and mark-to-market pricing.

This pattern is similar to:

2007 – Bad assets rise, spreads widen, while equity indices remain relatively calm.

2008 – Markets considered cash equivalents (like auction-rate securities) suddenly freeze.

In addition:

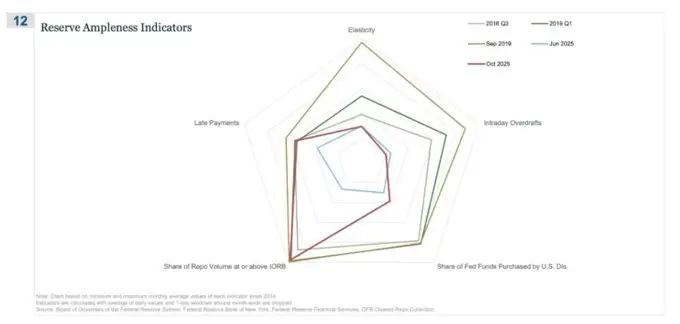

Fed reserves are peaking and starting to decline.

There is growing recognition within the Fed that some form of balance sheet expansion may be needed to prevent problems in the financial plumbing.

None of this guarantees a crisis. But it fits a system where credit is quietly tightening, and policy is still framed as "data-dependent" rather than preemptive.

The repo market (REPO) is the first place where the "not ample" story shows up

On this radar chart, "the share of repo trades at or above IORB" is the clearest indicator that we are quietly exiting the regime of truly ample reserves.

In Q3 2018 and early 2019, this indicator was relatively controlled: ample reserves meant most secured funding trades cleared comfortably below the IORB floor.

By September 2019, just before the repo crisis, this line spiked outward, with more and more repo trades clearing at or above IORB—a classic symptom of collateral and reserve scarcity.

Now look at June 2025 versus October 2025:

The light blue line (June) is still safely inside, but the red line for October 2025 extends outward, approaching the 2019 pattern, showing more repo trades are hitting the policy floor.

In other words, as reserves are no longer ample, dealers and banks are pushing up overnight funding rates.

Combined with other indicators (more intraday overdrafts, higher discount window usage, and increased late payments), you get a clear signal.

The K-Shaped Economy Is Becoming a Political Variable

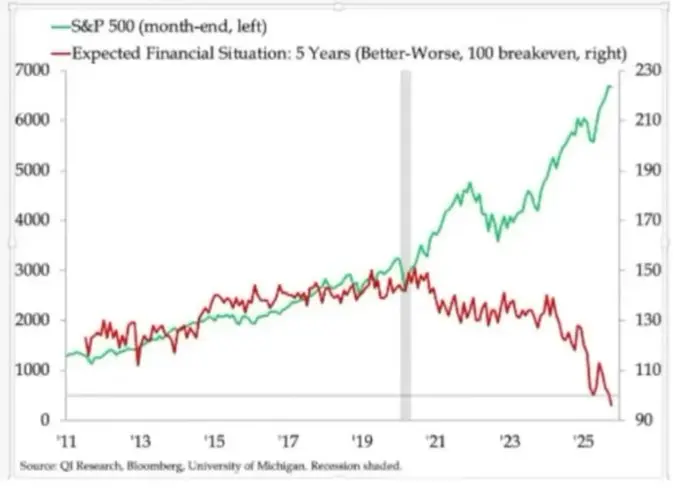

What we've long called the "K-shaped" economic divergence, in my view, has now become a political variable:

Household income expectations are polarizing. Long-term financial outlooks (like 5-year expectations) show a stunning gap: some groups expect stability or improvement; others expect sharp deterioration.

Real-world stress indicators are flashing:

Default rates are rising among subprime borrowers.

The age of first-time homebuyers is being pushed back, with the median age approaching retirement age.

Youth unemployment indicators are rising across multiple markets.

For a growing segment of the population, the system is not just "unequal"; it is failing:

They have no assets, limited wage growth, and almost no realistic path to participate in asset inflation.

The accepted social contract—"work hard, get ahead, accumulate wealth and security"—is breaking down.

In this environment, political behavior changes:

Voters no longer choose the "best manager" of the current system.

They are increasingly willing to support disruptive or extreme candidates from the left or right, because for them, the downside is limited: "It can't get any worse anyway."

Future policies on taxation, redistribution, regulation, and monetary support will be made in this context. This is not neutral for markets.

High Market Concentration Becomes a Systemic and Political Risk

Market capitalization is highly concentrated in a handful of companies. However, what is less discussed is its systemic and political impact:

The top 10 companies now account for about 40% of major US equity indices.

These companies:

- - Are core holdings in pensions, 401(k)s, and retail portfolios.

- - Are increasingly leveraged to AI, exposed to the Chinese market, and sensitive to interest rate paths.

- - Are effectively monopolies in multiple digital domains.

This creates three intertwined risks:

1. Systemic market risk. Shocks to these companies—whether from earnings, regulation, or geopolitics (like Taiwan, Chinese demand)—will quickly transmit to the entire household wealth complex.

2. National security risk. When so much national wealth and productivity is concentrated in a few companies dependent on external factors, they become strategic vulnerabilities.

3. Political risk. In a K-shaped, populist environment, these companies are the most obvious focus of resentment: higher taxes, windfall taxes, buyback restrictions. They will face antitrust-driven breakups and strict AI and data regulation.

In other words, these companies are not just engines of growth; they are also potential policy targets, and the probability of becoming targets is rising.

Bitcoin, Gold, and the Failure (Temporary) of the "Perfect Hedge" Narrative

In a world full of policy mistake risk, credit stress, and political instability, one might have expected bitcoin to thrive as a macro hedge. Yet gold has performed like a traditional crisis hedge: steadily strengthening, low volatility, and increased portfolio correlation.

Bitcoin's trading has behaved more like a high-beta risk asset:

- - Highly correlated with liquidity cycles.

- - Sensitive to leverage and structured products.

- - OG long-term holders are selling in this environment.

The original decentralized/monetary revolution narrative remains conceptually compelling, but in practice:

- - Today's dominant capital flows are financialized: yield strategies, derivatives, and volatility shorting.

- - Bitcoin's empirical behavior is closer to tech stock beta than to a neutral, robust hedge.

- - I still believe there is a reasonable path for 2026 to be a major inflection point for bitcoin (next policy cycle, next stimulus wave, and further erosion of trust in traditional assets).

But investors should recognize that at this stage, bitcoin does not provide the hedging properties many hope for; it is part of the same liquidity complex we are concerned about.

Scenario Framework Toward 2026

A useful framework for the current environment is: this is a managed bubble de-leveraging, designed to create space for the next round of stimulus.

The sequence may be as follows:

2024 to mid-2025: Controlled tightening and stress.

- - Government shutdowns and political dysfunction cause cyclical drag.

- - The Fed leans hawkish in rhetoric and balance sheet, tightening financial conditions.

- - Credit spreads widen moderately; speculative sectors (AI, long-duration tech stocks, some private credit) absorb the initial shock.

Late 2025 to 2026: Re-engagement with the political cycle.

- - As inflation expectations fall and markets pull back, policymakers regain "space" to ease.

- - We see rate cuts and fiscal measures calibrated to support growth and electoral goals.

- - Given the lags, inflation consequences will appear after key political milestones.

Post-2026: System repricing.

- - Depending on the scale and form of the next stimulus, we will face a new asset inflation cycle with greater political and regulatory intervention, or more abruptly confront issues of debt sustainability, concentration, and the social contract.

This framework is not deterministic, but it fits current incentives:

- - Politicians prioritize re-election, not long-term equilibrium.

- - The simplest toolbox remains liquidity and transfer payments, not structural reform.

- - To use the toolbox again, they first need to squeeze out some of today's bubbles.

Conclusion

All signals point to the same conclusion: the system is entering a more fragile, lower-tolerance phase of the cycle.

In fact, historical patterns suggest policymakers will ultimately respond with massive liquidity.

But entering the next phase first requires experiencing:

- - Tighter financial conditions

- - Rising credit sensitivity

- - Political turmoil

- - Increasingly nonlinear policy responses

"Original Link"