Content Token Boom: Is Base's "Creator Economy 2.0" a Revolution or Just Another Game for Whales to Profit From?

Content Coins may be the only way for Rollups to truly excite creators. But be aware: the house always wins.

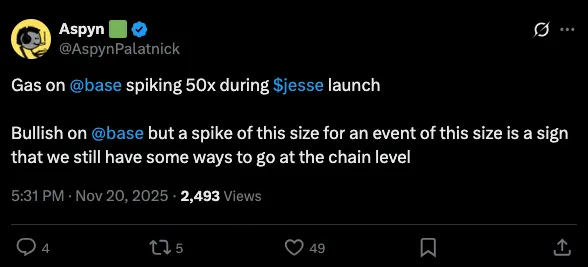

Crypto Twitter’s reaction to the launch of $JESSE was not friendly:

(In fact, the tweet above is one of the more rational and down-to-earth criticisms I’ve seen.)

Others have pointed out some issues:

- Poor timing: The launch coincided with an article by David Phelps, in which he complained that Base was too focused on creator tokens;

- Extraction issue: Some believe $JESSE took a large cut of transaction fees from sales;

- Sniping issue: Because $JESSE used the Zora x Doppler bonding curve auction mechanism, it unexpectedly attracted snipers.

But I don’t agree with these concerns.

The timing issue is indeed a bit unfortunate, but I suspect Jesse had long planned the launch date and chose his own birthday as a special milestone.

The extraction issue also doesn’t hold up. During his birthday livestream, he was able to reinvest the fees into other creators on Base. He also claimed he did not intend to sell these tokens.

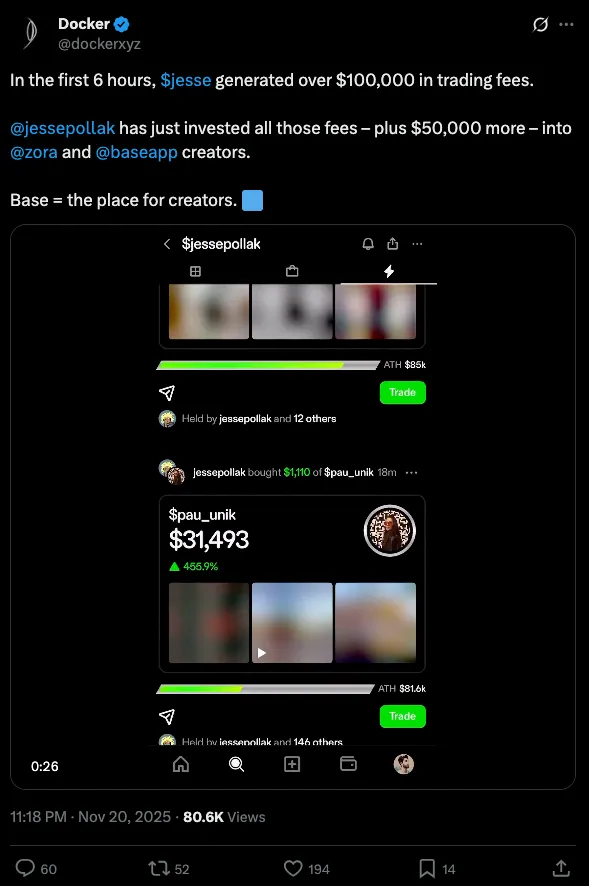

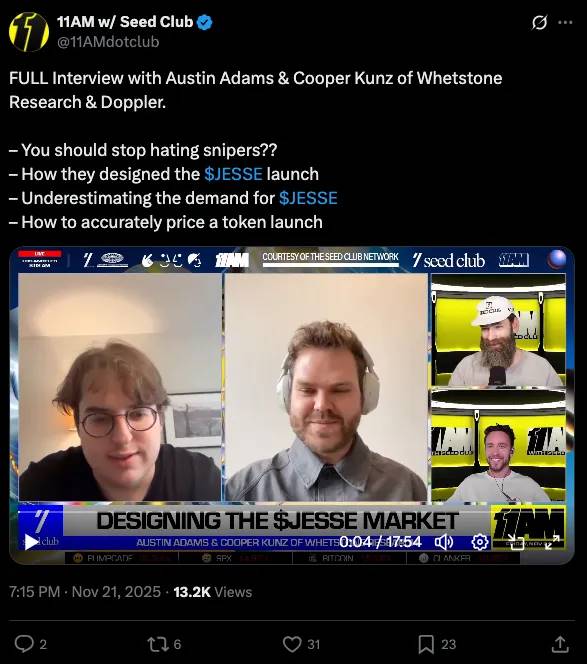

Ultimately, Doppler and 11AM had a pretty good discussion about the sniping issue:

We’ll dive deeper into the pros and cons of different auction mechanisms in next week’s content, but Austin’s research on auction mechanisms far exceeds those simply complaining about sniping on X (formerly Twitter).

If it’s not out of malice, then why did Jesse do this?

The Real Reason for Pushing Creator Tokens

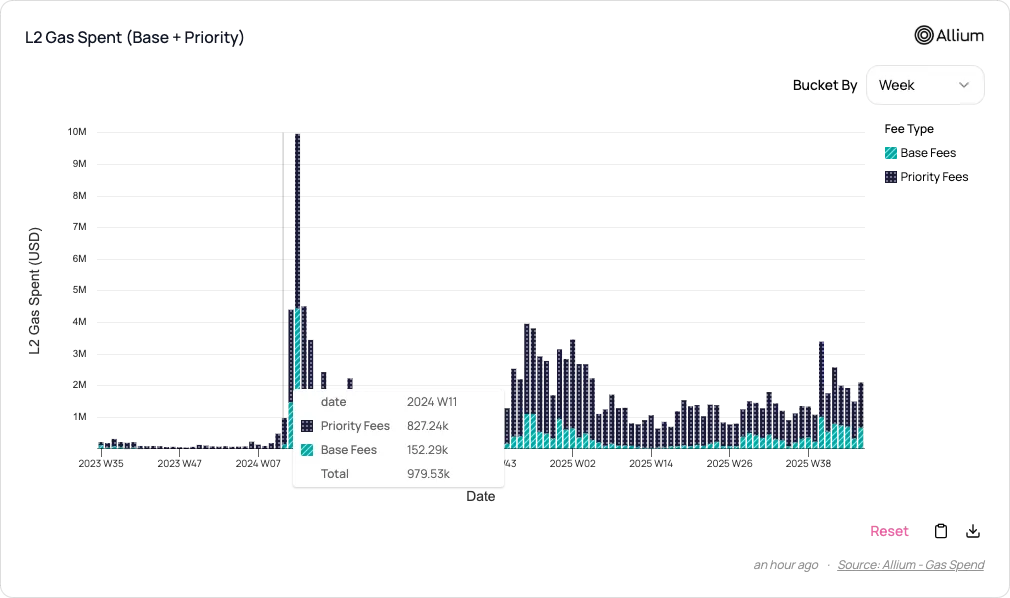

Most of a Rollup’s sequencer revenue comes from transaction fees.

So far, Base has earned more revenue from meme token trading than from any other activity. The issuance of new tokens and the resulting speculative trading volume are key drivers of transaction fees.

Source: Allium

It’s very likely that Base is spending more than ever on core team, grants, events, proprietary apps (like Base App), and support for founders. But these expenses haven’t significantly increased Base’s contribution as a Rollup to Coinbase’s financial statements.

Creator tokens and content coins are a very clever solution to this problem:

- Their issuance volume even exceeds that of meme tokens (token issuance is the main battleground for Rollups);

- They can stimulate trading and speculation;

- They are built by converting attention into on-chain fees—anything that goes viral can be tied to a content coin;

- Compared to meme tokens, they don’t even require any underlying economic activity, community support, or commitments.

Although users see skyrocketing gas fees as a negative, from the Rollup’s perspective, creating excessive demand for block space is actually a sign of success.

No other form of creator monetization achieves the same effect:

- Payments: Any form of payment (such as donations) generates insufficient transaction volume, especially the portion paid to creators.

- Rewards: Base does use reward mechanisms to support the Base App ecosystem, but these rewards have a negligible impact on revenue.

- Advertising: On-chain advertising is virtually non-existent, so it cannot contribute to sequencer fees.

Are Creator Tokens Really Good?

We now understand why creator tokens are a key focus for Base, but are they really the best mechanism for users and creators?

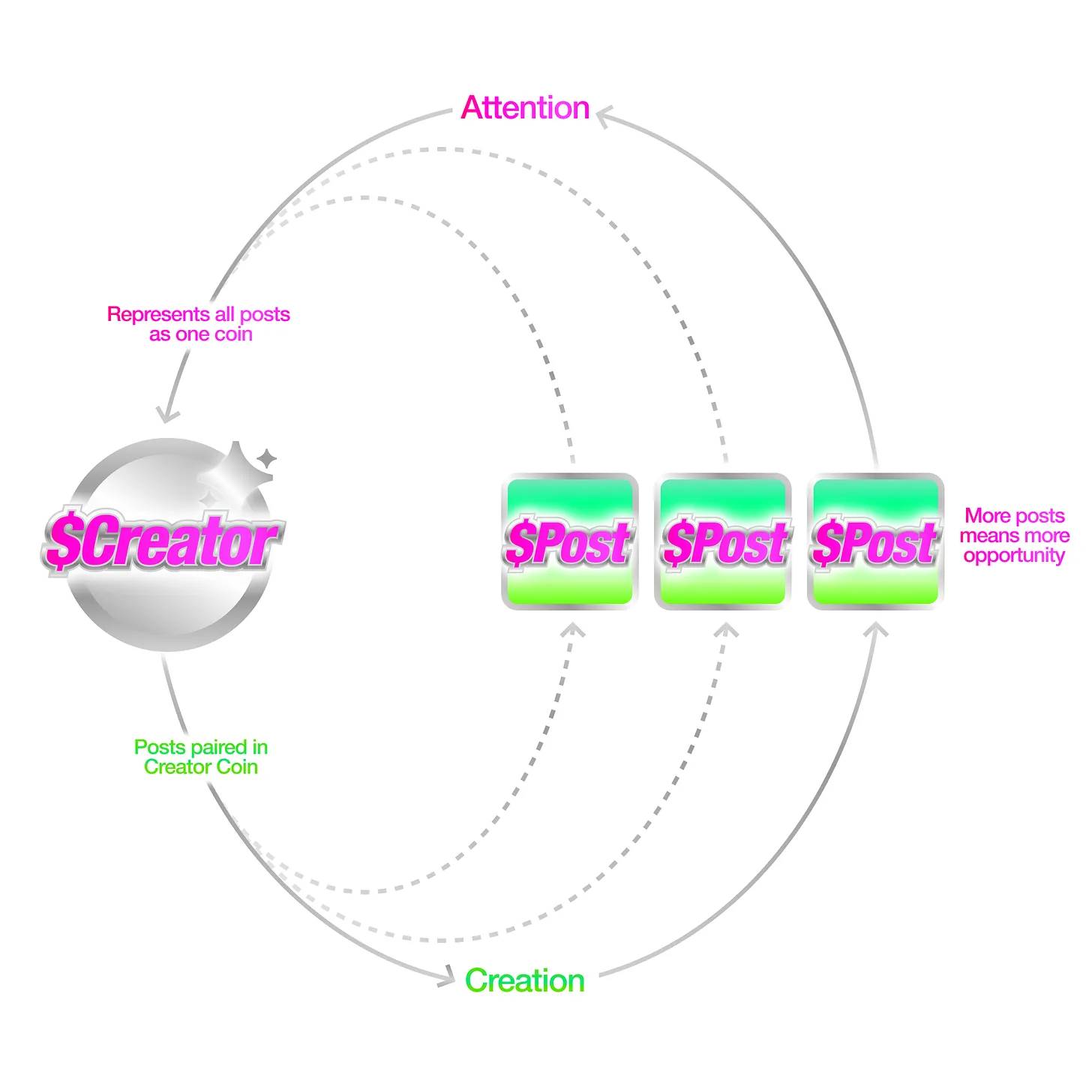

Source: Zora Docs

The flywheel logic of creator tokens is simple:

- If you publish content, a content coin is generated, and you own 1% of its supply.

- Each content coin can only be purchased with your creator coin. If you issue a creator coin, you hold 50% of its supply (gradually unlocked).

- Demand for content coins naturally drives demand for creator coins. This mechanism incentivizes you to create high-quality content while benefiting from holding creator coins and transaction fees.

In some ways, content coins behave similarly to Patreon memberships. If you spend $1,000 to buy a content coin, your opportunity cost is the return you could have earned by investing that $1,000 elsewhere. The foregone return is essentially like paying a creator subscription fee. In return, the creator may reward you for holding these coins. These rewards can be tiered like Patreon, or distributed proportionally or randomly (like a lottery).

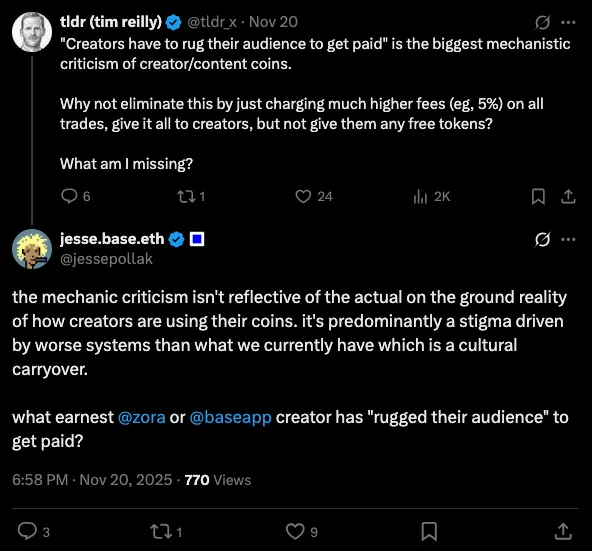

However, creators cannot directly receive subscription fees unless they sell their own creator coins. So, even if your cost is paid in the form of a yield subscription, not all of it effectively transfers to the creator you support—unless they “cash out and run” (i.e., “rug”). Jesse also pointed out this issue:

Additionally, content coins have a fan collectible attribute. As an artist’s popularity grows, the rewards they can offer “subscribers” become more valuable. Thus, content coins have a speculative component. Even if you don’t care about supporting the artist or getting rewards, you might buy content coins just to speculate on the potential future value of those rewards (whether tangible or intangible). This is similar to buying a first edition CD from your favorite artist, which you might resell at a higher price in the future.

However, this feature of creator tokens also brings significant drawbacks: they have essentially become financial instruments, and their market may attract institutional participants with more advanced tools than ordinary fans.

Just as true fans need vision, patience, and investment to identify, preserve, and invest in classic CDs or merchandise, the content coin market also needs real fans for support. On the other hand, a savvy trader can profit from content coins simply by sniping or other speculative means.

When exiting “membership,” you need to sell the tokens, which incurs slippage. Ironically, the lower the liquidity of a creator token, or the greater your contribution to the creator, the higher the slippage you face. In some ways, content coins punish the most generous sponsors.

The House Always Wins

My core issue with the creator token model is that it tries to combine sponsorship and curation to maximize trading volume, but may bring out the worst of both worlds.

- True sponsors have to deal with price volatility, adversarial market participants, transaction taxes, and more.

- Curators lack clear guarantees of future rewards, since creator tokens are not explicitly tied to creator equity or other value streams. Curators are essentially speculating on potential demand for unknown future rewards.

- This model tends to front-load creator income, potentially generating large transaction fees during the initial price discovery phase, but it’s uncertain whether long-term trading volume is sustainable (the performance of $JESSE will be a case to watch). This mechanism does not truly align incentives between creators and token holders.

The end result is that the underlying blockchain and trading venues (in this case, Uniswap) extract far more revenue than a simple membership payment solution would.

You could argue that curation markets do provide an additional function, but the two (sponsorship and curation) cannot be clearly separated.

As a comparison, we can study Craig Mod’s model. He built his own membership system, focused on keeping the setup as streamlined as possible, and succeeded.

He can proudly say that no one has lost their hard-earned money by supporting him.

What attracts me to Craig’s model is that it focuses on the act of creation itself (such as books), not on content or the creator as a person.

Personally, I believe that a creator economy centered on interaction is inferior to one built around real value exchange. Content should merely be a discovery mechanism and a way to create publicly, not the core product. To some extent, a free basic tier can be provided for users to experience.

I also believe these problems can be solved, and there’s no doubt that the Zora and Base teams are working hard on this.

At the very least, creator tokens represent a brand new attempt at creator monetization. Even if it doesn’t ultimately become the optimal solution, it’s still worth trying.